Masculinity

MASCULINITY

SCROLL DOWN

Masculinity

MASCULINITY

"Masculinity"

This series is an exploration of the projected identity of the human male, as such, it is intended to include a full range of emotions and gestures. I am enthralled by the painterly effect achieved by photographing the male form through water, the way the forms seem to radiate carnal energy. Beyond that, I have decided to leave the interpretation more open than I had initially planned.

"Paintings"

"PAINTINGS"

"Paintings"

"PAINTINGS"

Artist Statement

Jill Greenberg, 2015-2022

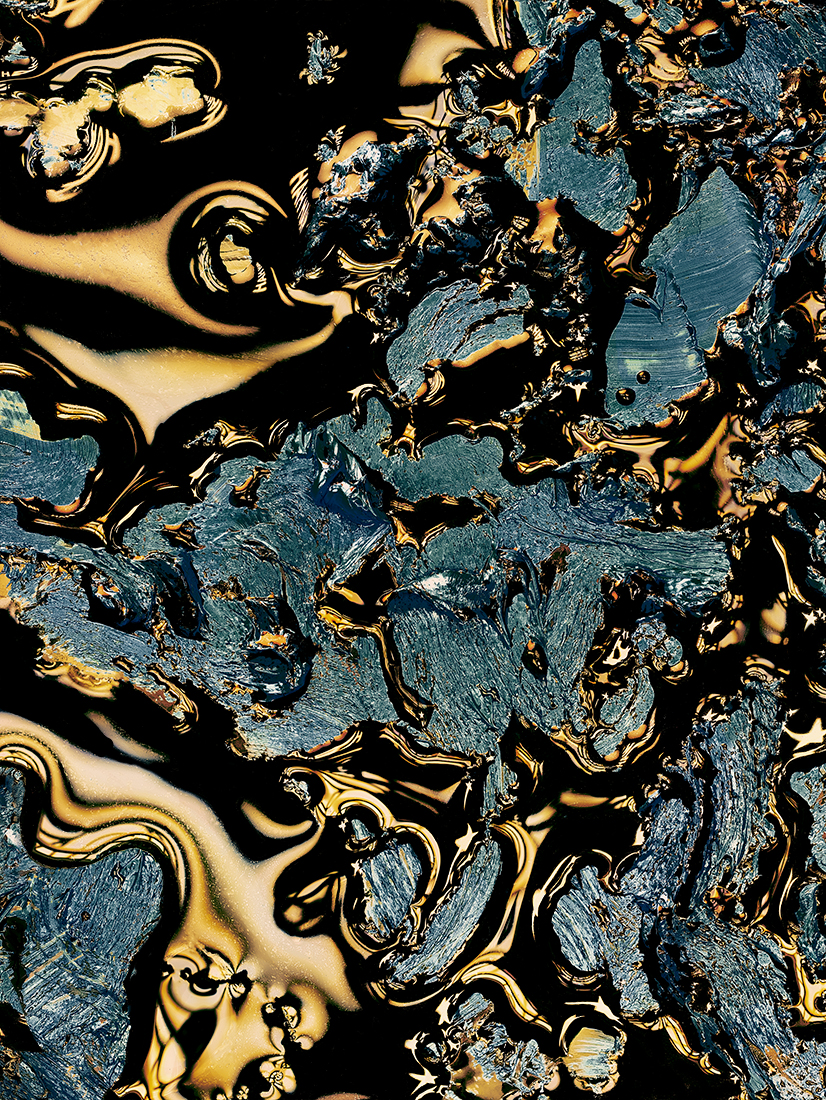

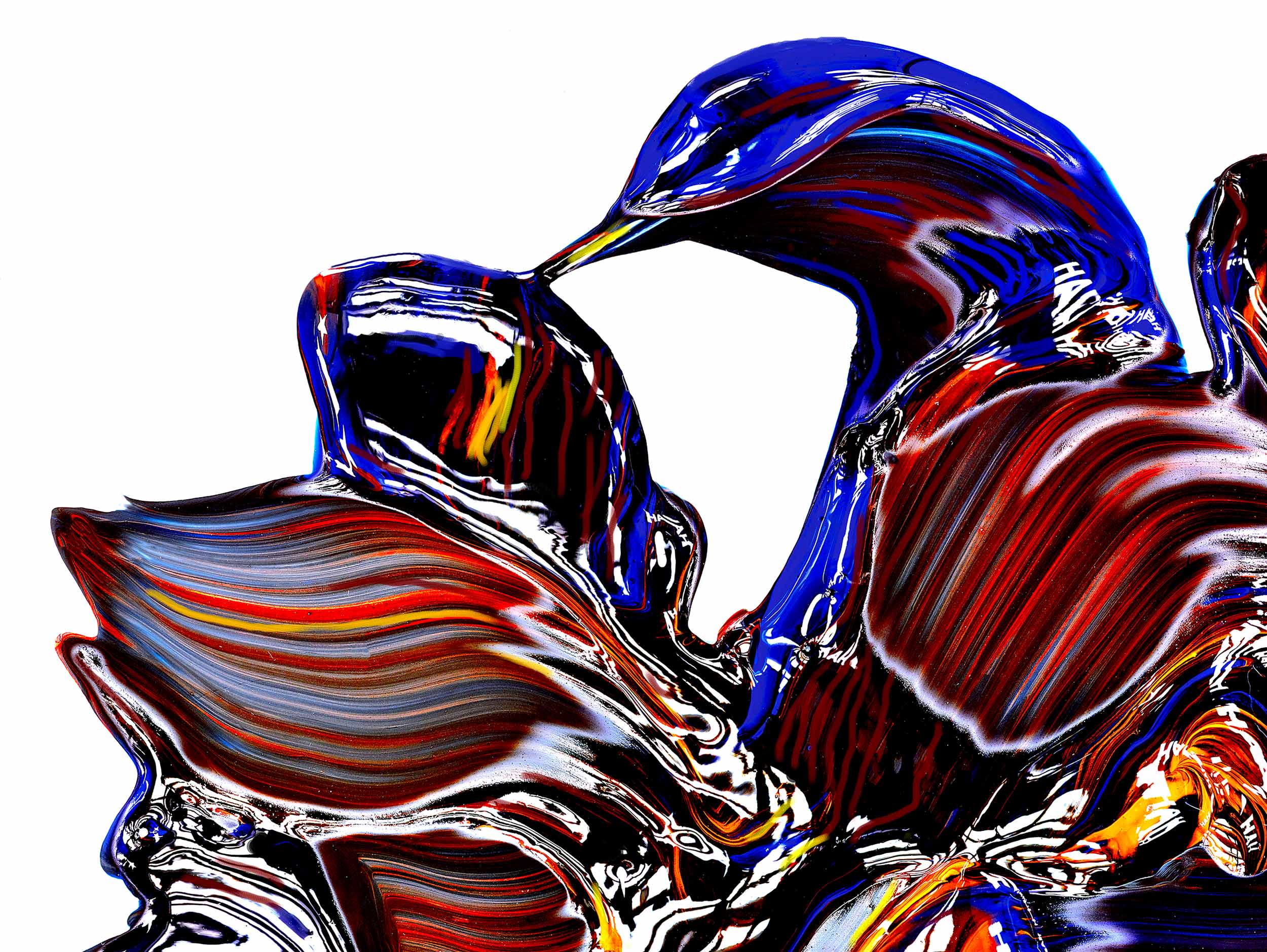

These are photographs of actual paintings that I make by hand. There is no CGI or Photoshop.

The ”Paintings” series was motivated by a turning-of-the-tables on painters who use found photography as their source material, and those who find the need to re-render appropriated photography.

So I set out to make a body of work that commented on this cliche of paintings of photographs. Yet ultimately, as with all of my work, I aim for the work itself to not only have meaning but also be luscious and compelling, vivid and emotional. I combine acrylic, tempera, oils, and water, usually on a glass painter’s palette. By manipulating the paint with brushes and palette knives, allowing it to dry, adding water back, and rotating the glass to change the reflections, as I capture images remotely from my laptop, each sequential capture is slightly different as the water flows and the pigment dissolves, the surface of the paint reflecting light differently- creating suites of images.

Then, to modulate the lighting, I employ both natural light from my studio skylights as well as studio strobes with soft boxes and hand-cut stencils which then cast shapes or words visible in the paint's reflections.

There is very little retouching—primarily cleaning up dust caught in the wet paint. The image data is quite processed via the image capture program: adjusting contrast, hue, and sharpness, and utilizing almost every slider for maximal effect. Lately, I have allowed myself more freedom with the post, since it was an arbitrary constraint.

This is a simulacrum of impasto. Lens-based, 100-megapixel paintings. Hand-made and high res.

Process is everything, and does not look like much of anything in real life; the majority of the effect is lighting, reflection, and image processing. Many have been upset that I toss the painting used to make these images and that I wash away the original, but this painting, once dry and without all the punched-up contrast, looks nothing like the final works. The value of the destroyed paintings still haunts the confused audience who feels that painting is the fairest form of art in the land. But one would not save a moldy bowl of fruit or rotting flowers that were painted as a still life. Here, the photograph is the culmination of the work, the new medium made with a mastery of both light and paint, time and the hand, not a mere painting.

The handmade mark was something I truly missed and had been trying to bring back into my work for many many years, I had experimented in all sorts of ways with painting on prints, and photographing paint in daylight when I lived in LA, but it was the latticed almost fractal-looking reflections in the wet paint from my Chelsea skylights that allowed for this breakthrough. I work for hours straight, the changing light and clouds affects the image and I adjust my camera exposure to the painting, I love it so much. The best part is that I can add a mark and not be afraid to ruin the painting, since I have already captured it as a photograph.

___________

"Paintings"

Featured Exhibition in Scotiabank Contact Photo Festival 2016

Essay by Erin Saunders for Bau-Xi Photo Gallery, 2015

Bau-Xi Photo is pleased to present “Paintings,” a bold new series by acclaimed photographer Jill Greenberg. Known internationally for her playful portraits, signature lighting and post‐production techniques, Greenberg now experiments with painting as her photographic subject, a venture that radically challenges ideas about medium, process, and originality. These “Paintings” are single‐edition archival ink prints that study the interaction of light and painted surface: high gloss, still‐wet smears of gouache ooze; brushstrokes are blown up to reveal multi‐dimensional colours mixing over the palette. The final photograph—made unique by Greenberg’s destruction of the initial painting—flattens the surface, crops its organic spread, and magnifies its properties. Greenberg’s images are intense visual stimuli that seem to push paint to its absolute limit as it begins to verge on the surreal—all that is missing in the finished product is the paint itself. “Paintings” are engrossing images that at once indulge and deny our senses, provocative surfaces in which paint and photography are each other’s muse.

Jill Greenberg’s recent series “Paintings” has regularly been described as the artist’s return to the medium with which she began her studies at the Rhode Island School of Design in the 1980s. But “return” may be too simple a term. Indeed, “Paintings” might be seen as an extension—even a culmination—of the acclaimed artist’s experimental photographic practice, one that profoundly unsettles expectations about medium, process, and authenticity.

Whereas art history once grappled with the questions of what painting could offer photography beyond the promise of imitation, Greenberg’s images insist on a kind of reversal: what does photography offer painting? Even more, in what way does each medium extend the other’s limits? Greenberg’s career has certainly explored these boundaries in her accomplished commercial career, in which post‐production techniques—now celebrated and widely emulated—feature heavily.

For “Paintings,” Greenberg begins her process by applying a range of paint types to a glass palette, manipulating both dry and wet pigments to create dynamic surfaces of pure colour and texture. She then photographs these painted experiments under both natural and artificial light sources, sometimes using stencils that reflect words and shapes onto the surface. The process is a paring down of both media to their essential elements: mixing and blending on the artist’s palette meets the process of filtering and directing light. Once her image is captured, Greenberg discards the painting, effectively eliminating—but also complicating—the notions of subject and source.

The result is a large format art object—an archival inkjet print, sometimes on printed on and stretched on canvas—that reveals stunning chromatic dimensions and dramatic range of consistency in Greenberg’s initial painting, while also depending fully on the almost fetishized finish that the camera provides. The artist’s lighting techniques capture the high gloss of a still wet smear of gouache in provocative displays of texture and tactility; at the same time, the photographic layer flattens the painted surface, cleanly crops its organic spread, and magnifies its properties to hyper‐realistic effect.

Greenberg’s “Paintings” lend the reproducibility of photography to the perceived uniqueness of painting, while also denying this same reproducibility by creating unique, single‐edition art objects. The process is a sophisticated comment on how the myth of authenticity struggles to coexist with the essential construct of commercial copyright. “Paintings” are not paintings, nor are they photographs: they are moments of painting—studies of visual material under highly controlled of conditions; they are vehicles for photography—surfaces for experiments of light. In many ways, this collapsing of media is not a return to painting so much as it is a departure from art historical terminology altogether. Greenberg’s images radically call into question the hierarchy of media that has described artist practice since the mid‐1800s, and incite new questions about the ways we consume and interpret visual information: has Greenberg rendered all painting site-specific; has she re‐inscribed photography with aura? The anxiety that comes with such questions are aptly represented by the scare quotes on either side of the series title; “Paintings” is a placeholder for something else, something new, something we cannot yet put words to.

IONOGRAPHS

IONOGRAPHS

IONOGRAPHS

IONOGRAPHS

About Ionographs

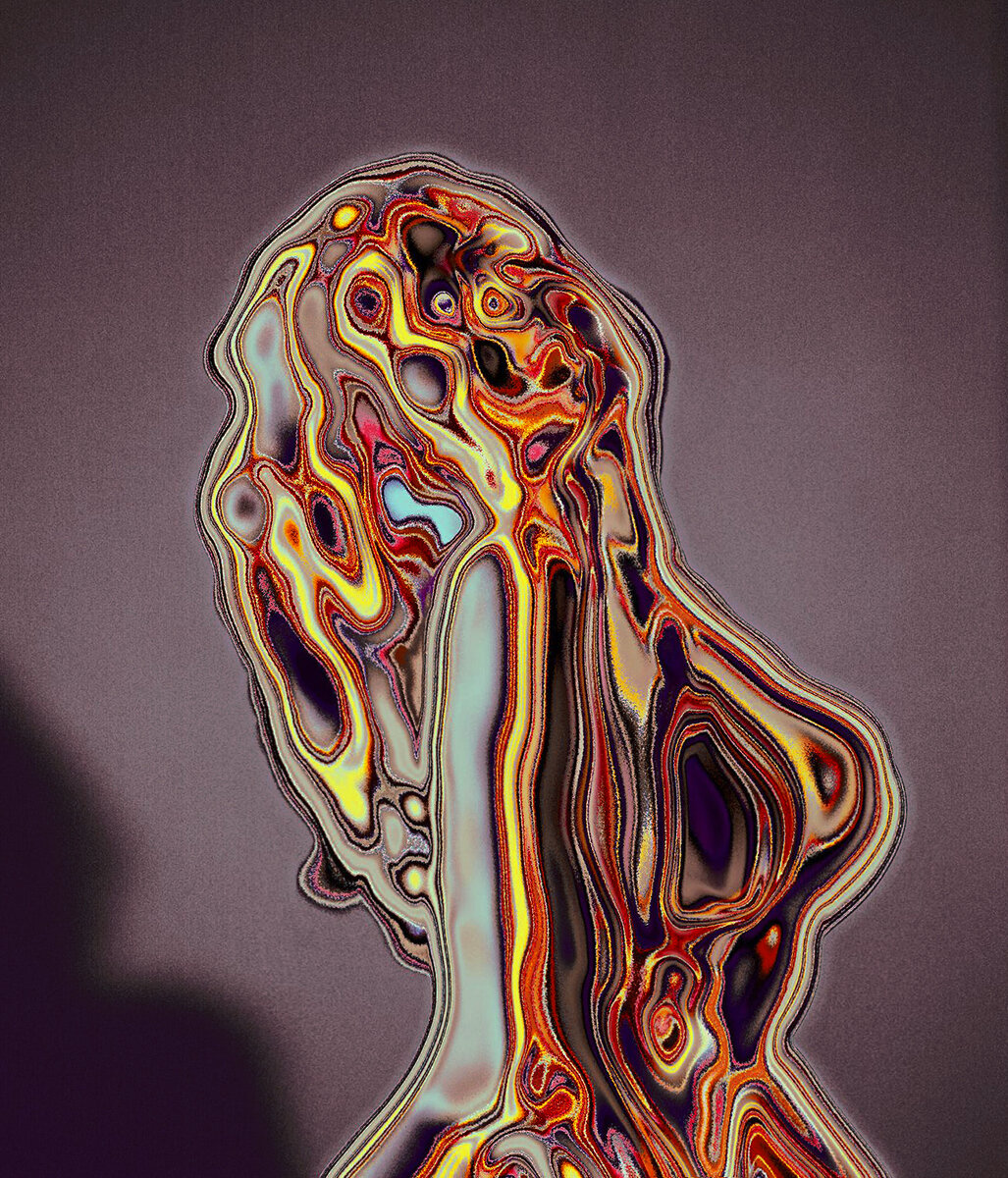

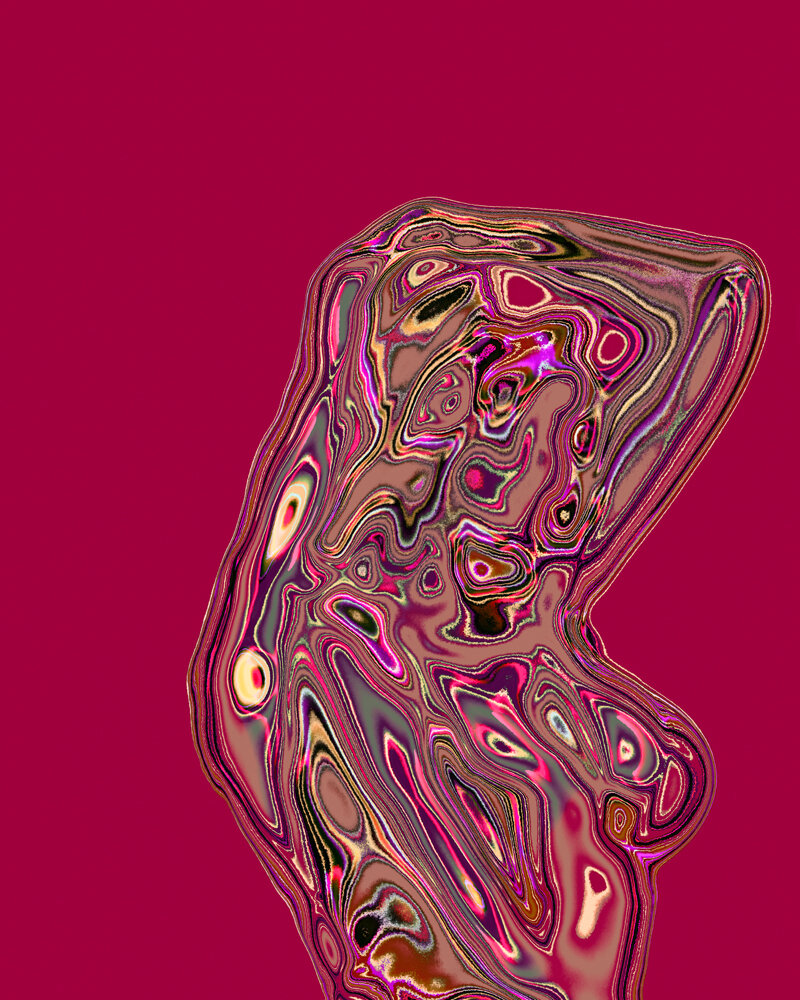

2018-2020

Algorithmic ciphers, "Ionographs" suggest the continued battle between handmade vs machine-made, "representation" and an alien figment of the unconsciousness. On one hand, these images are massive digital files-100 MP captures of the light reflected off physical forms which actually presented themselves in the artist's studio yet, on the other hand, the software's algorithms have been jacked. Images that seem to offer data, which evoke heat maps or some other data visualization technique, have been manually scrambled to ablate the subject's individuality and obfuscate the portrait.

Horse

HORSE

Horse

HORSE

Horse/Power

Jill Greenberg, 2013

My obsession with horses began at the early age of six. What is it that makes young girls project so much onto these gorgeous animals? I drew them, painted them, sculpted them, collected plastic models of them, read stories about them, and rode them. When I saw the same happening with my young daughter, I decided it was time to return to my primary muse. It had been more than thirty-five years since my first attempts to capture the grace and musculature of these animals, and I finally had a black beauty in the studio and the skill to render him completely. Just to see the magnificent creature standing outside his trailer was beyond exciting. Those of us who live in cities easily forget the scale and power of large animals.

The horse project is not only an homage to the physique of these sexy beasts but also an exploration of the paradoxical gender identities cast onto this unique animal. We see them as masculine, strong, muscular, even phallic. Yet they have been made subservient, so their position in the world relates to the role women continue to occupy. Horses are both masculine and feminine, dominant and submissive, mastered and wild. Their raw power and their innate sexual energy are harnessed by both men and women. My photographs focus on the animal’s body; on cut, striated muscles under shiny, cropped hair; on crimped manes and windswept forelocks; on the strong shoulders and hindquarters of Baroque breeds like the Friesian and the Andalusian. The colors I digitally hand-painted are associated with the feminine, yet the formal approach and strength portrayed is decidedly masculine.

But the horse’s rich history of ownership and usefulness to humankind comes out of an equally long history of forced submission. Horses must submit to the bit. Until quite recently, it was universally accepted that horses needed to be “broken” by their owners. The bit is a piece—or multiple pieces—of metal that interface with the tongue and mouth. An aggressive rider will yank the reins, which pulls the bit deeper into the mouth, gagging the animal. Items of tack called martingales, which tie the head down and force it to stay low, with the neck arched, are used to win points in dressage tournaments. This is called rollkur, or hyperflexion. Several images in this book show rollkur, but the position had been prompted by no tools save a carrot to encourage and direct the horse’s head. There are special bridles for jumping events that even shut horses’ mouths completely. The bits and bridles are used to control and manipulate raw, natural power, much in the same way that women’s movement-restricting apparel, supporting undergarments, and especially high-heeled shoes can be painful and limiting. I photographed bits, which, when taken out of context, suggest the appearance of sadomasochistic bondage gear. Which is, in fact, what they are.

My research into the harsh practices of equestrian oppression led me to discover a similar tool for use on women dating to the 1600s, called a scold’s bridle, designed to punish and silence mouthy women. The bridle was equipped with not only a serrated piece of metal to be inserted into a woman’s mouth but also, at times, with large ears so that the woman resembled an animal, to further the victim’s humiliation as she was paraded around on a lead in public.

British scholar Gavin Robinson has written about the horse as central to power in past cultures:

"Some punishments were very heavily gendered. The scold’s bridle symbolized the idea that women were like animals, because horses were made to wear bits and bridles. But there was also the practical effect that the bridle stopped a woman from speaking. Speech was said to be one of the main things that set humans apart from all other animals. By taking away her power of speech the bridle made a woman more bestial in practice as well as in theory."

Ultimately, I uncovered an historical incident that both signifies and transcends: a moment that has become a locus in my work to spotlight the intense emotion associated with the continued failure of feminism. The account is that of Emily Wilding Davison, a highly educated British suffragist. In 1913 she walked onto the Epsom Derby racetrack in the midst of a horse race in an attempt to pin a symbolic suffragist flag on a horse, but collided with and was trampled by Anmer, King George V’s horse.

In that one visceral moment, the idea of the horse and the idea of feminism manifested itself for posterity, in a woman’s failed effort to halt the forward motion of the animal of the most powerful man in the land—his surrogate, his racehorse. Recent work has led me to sketches for a sculpture to commemorate this event. A monument to the failure of Feminism. Interestingly, a life-size statue commemorating Emily Wilding Davison would also serve to remind us that, in the United States, only one in eight statues celebrate a woman’s achievements (Harper’s Index May 2011).

But more on the form of the horse. Their heads and necks are remarkably phallic, and I have chosen to exploit this in my photographs. I have long been concerned with “exposing the phallus” in a playful, mocking way. The horse’s neck is presented as a confrontational image. In general, the shapes and features in the photographs are not manipulated at all. The extent of the digital imaging work that I do varies, but it is primarily concerned with changing color, shading, and shine. These animals were photographed in makeshift studios set up in the ring at stables in and around California and outside Vancouver, as well as running free outside their barns. I used a camera better suited for studio portraiture so as to capture the highest-quality image possible. Chasing untrained horses with multiple, flashing strobe lights popping wasn’t the safest way to take photographs, but I survived, and it was worth it.

Glass Ceiling

GLASS CEILING

Glass Ceiling

GLASS CEILING

Artist Statement: Glass Ceiling

By Jill Greenberg, 2011

The “Glass Ceiling” project is about the “set up” of being a woman. These women are professional athletes and dancers; therefore, they are dressed for work. In 2008, I was commissioned to do a “fashion” shoot using the US Olympic Synchronized Swim Team as models. Two of the set ups included high heels for the athletes.

It was when I saw an outtake, where a solitary woman floated rigidly, the surface of the pool slicing her neck, that I thought: this embodies the glass ceiling! Later, I found a local synchronized swim troupe in 2010 to continue this exploration: I directed the women to perform specific gestures as I sat at the bottom of a pool in full scuba gear with a then state-of-the-art 65 megapixel back on my digital camera.

The force and heavy weight of the water knocks them into awkward positions. The high heels- which were part of the synchronized performers kit- amplifying their lack of control in this underwater world.

“The disciplinary project of femininity is a setup, it requires such radical and extensive bodily transformation, that a woman is destined in some degree to fail.”

This quote by Sandra Lee Bartky was the crux of my senior thesis, “The Female Object” at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1989. At the conclusion of the multimedia presentation that was the “Female Object,” the final projected slides declared “Your Freedom from the Corset is an Illusion”, “Exit the Powder Room.” It was my assertion that this project of femininity is a self-created distraction from accomplishing more serious goals.

“Glass Ceiling” marks for me the return to my explorations throughout the 90's of the depiction of the female body as if directly channeled from internalized patriarchal male gaze. In these images, the identities have become inconsequential as their heads are cut off, the sexualized bodies are the focus. As a female artist, I have experimented with imagery which explores the objectification of women for many years. First, a series of drawings of women as seen by men, just breasts, vaginas, heels, then a multimedia digital piece commissioned for RSUB in 1996, called "Eve of the Future" which posited that if man could genetically engineer the woman of his dreams, she would have multiple orifices and no head. This work was later acquired as part of a collection by SF MOMA.

The images channel the feelings I have of being powerless in a culture run by men. The psychic violence is made pictorially overt. The subjects are victimized despite their physical strength, health and any other good luck they might have been born into. The fact that they had the bad luck of being born women makes them a punchline. The violence in our slang and street vernacular used in discussing women and sexual intercourse makes it apparent that the collective male culture feels aggressively dismissive of women. I felt it was important to show the violence and emotion I feel as a woman in contemporary culture, from a woman's point of view. The images might be read as violent towards women, they are meant to be. This is what it feels like to exist in the female body.

End Times

END TIMES

End Times

END TIMES

End Times: Epilogue

By Jill Greenberg, 2012

When I set out to create my series of crying children in 2005, I had no idea that it would cause such a stir in both the photography and cultural community at large, or that the images would be so widely appropriated for causes significantly at odds with my original intent.

Each image in the series, which I entitled “End Times”, was created by eliciting a child’s hyperbolic reaction to extremely minimal provocation. In many cases, the very young subjects (children ages 2 to 4) required no provocation at all, and were simply agitated by the act of being photographed. The reasons for their distress were common to those of any child: having something taken away. As any parent knows, rarely does a toddler sobbing convey any real pain or mental anguish. At that age, crying it is one of the main methods of communication, and in this particular instance, a short tantrum provoked by gentle manipulation. Indeed, I found the circular logic at play a striking paradox. The children’s worlds were not ending by having a lollipop taken away, but if only they had the capacity to understand what was happening to their world—to the environment—as a result of the backwards, conservative leadership in the White House in 2005, when the photographs were made, they would undoubtedly be distressed.

Before the exhibition in April, 2006, “End Times” was exhibited in a solo booth at the Scope art fair in New York. There, the work elicited no controversy. A few weeks later, a pseudonymous photo blogger—a banker by day—discovered the work online and wrote that I should be “arrested and charged with child abuse” for my techniques, an all-out polemic ensued. When American Photo magazine cited the blogger and called the work, “the most controversial photo series of the year” in their April 2006 print edition, the volume of online comments in response crashed their server. I was interviewed by BBC TV, Inside Edition, Good Morning America; was covered in The Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, The Sydney Morning Herald, and El Pais in Spain among others. The London Sunday Times magazine ran a six-page cover story called “The Great Lollipop Debate,” referring to one of the methods for making the children cry (the childrens' mothers or my photo assistants requesting the lollipops back.) While I had very much intended for my art to be provocative, I had no sense of the hornet’s nest into which I was poking a sharp stick.

Nevertheless the work itself garnered awards and was acquired by significant private collectors. “End Times” has been exhibited in solo shows in Los Angeles, New York, Paris, Adelaide, Australia, and in group shows at such venues as Brown University, the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art in Toronto, Boston University, and Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rome (curated by Paul Wombell).

Because of the influx of attention, the images have been widely published and have served as a sort of visual accompaniment to a host of causes, institutions and businesses wishing to play on the sympathy evoked by an image of a child in distress. I don’t license my fine art work for advertising, and very very rarely for editorial or web use, but the images became a sort of visual meme and were stolen and used rampantly without my or the models’ guardians’ consent. To date, the images have been used in anti-child abuse campaigns, political campaigns for the far right in Switzerland and the communist party in Estonia, and for advertisements for phone applications and life insurance, as well as for countless Facebook and Twitter avatars.

If asked, I would never have allowed for the images to be used for any intent and purpose other than that of my own. But I am seldom asked. Blogs dedicated to deconstructing “The Jill Greenberg effect”—my lighting and retouching techniques from the series—continue to pop up in such disparate languages as Arabic and German, and I’ve been told that photography students worldwide are being assigned to reproduce the images as part of their coursework.

The photographs have a life of their own now. I created them, and, like children, have ambivalently let them out into the world.

The Female Object

"THE FEMALE OBJECT" 1989

The Female Object

"THE FEMALE OBJECT" 1989

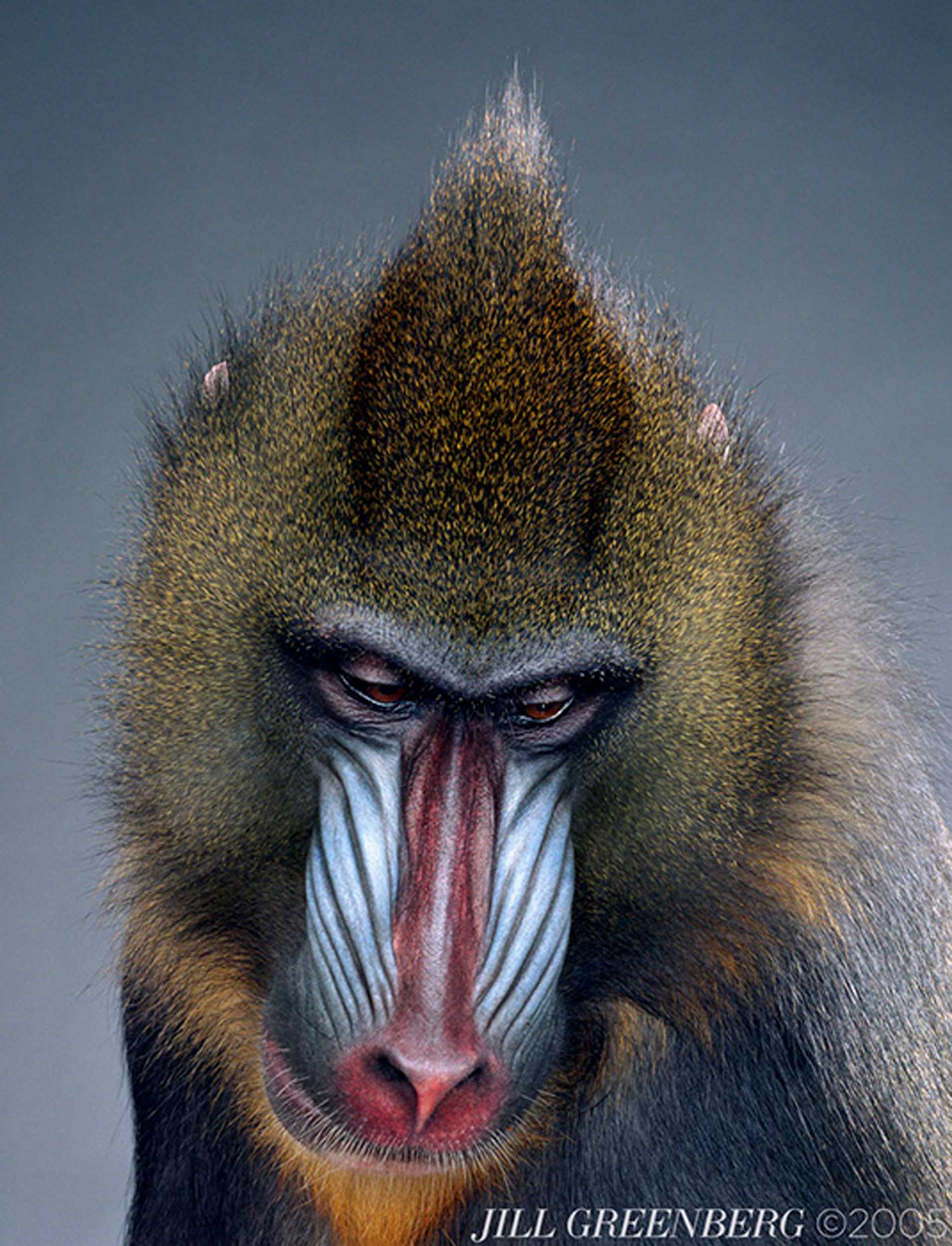

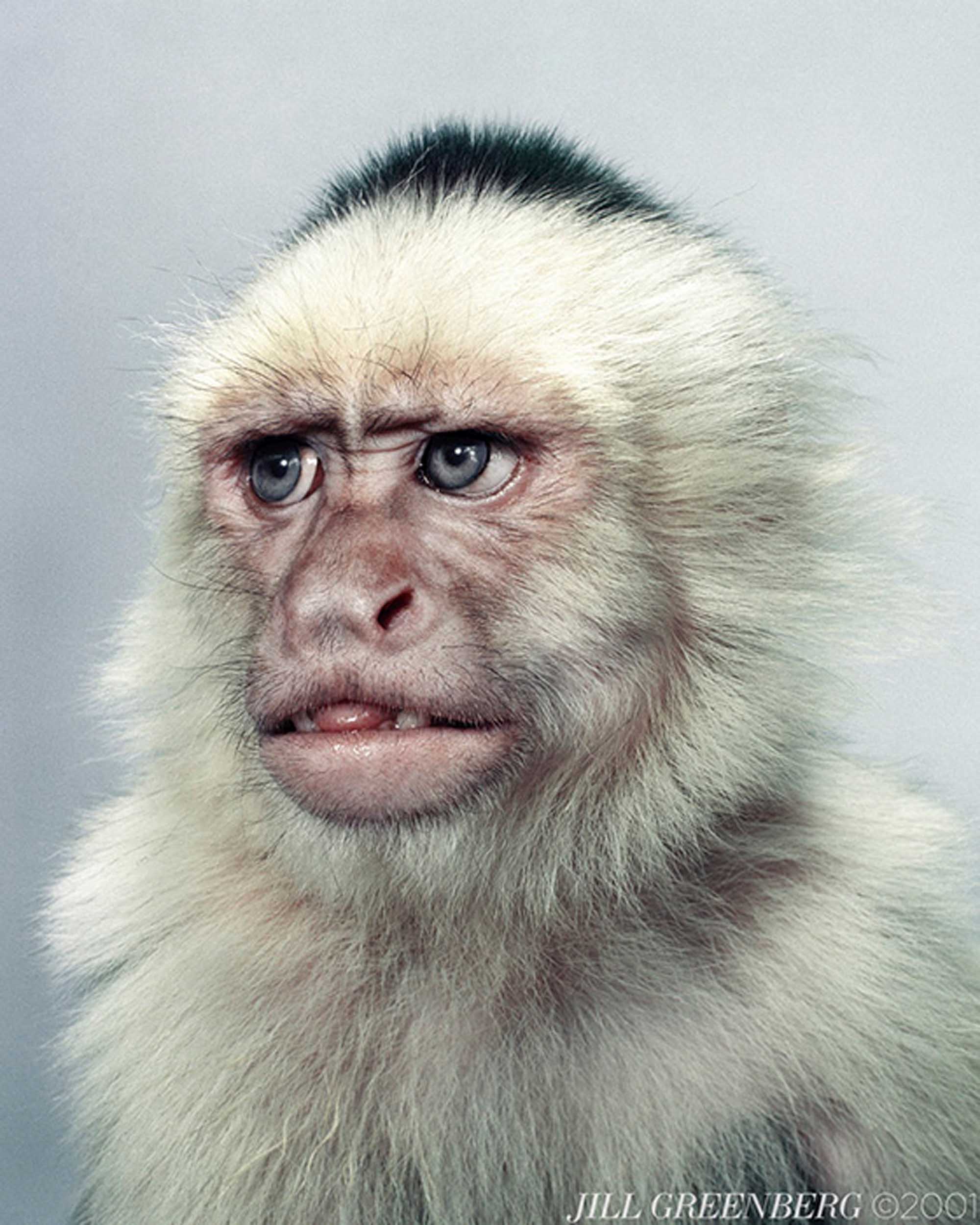

Monkey Portraits

MONKEY PORTRAITS*

Monkey Portraits

MONKEY PORTRAITS*

Monkey Portraits Artist Statement

By Jill Greenberg

I began photographing monkeys and apes by accident. I had booked a small white capuchin named Katie for an advertising job. She was supposed to be having a tea party with two little girls in a pink room, standing on the table banging pots and wearing pink striped bloomers. For other assignments, I had shot penguins, lions and albino pythons, but this was the first time I had photographed a monkey. Since I had a bit of extra time and a nice client, I decided to do a portrait of Katie.

When I got the contact sheets back, the images startled and amused me. Katie’s expressions were so human and her intelligence seemed so obvious I realized I had discovered a new subject - one perfect for social commentary. Since this work happened to commence in October 2001, just after the tragic events of 9/11, I was discovering my own sociopolitical awareness of the world. These animals’ expressions allow an interpretation that can be perceived as passing judgment on the behavior of their genetic cousins. Ultimately, I ended up having to reshoot the ad with a toy poodle, since the client decided the monkey looked too menacing – not quite the effect they wanted to sell to moms in the Midwest.

I photographed more monkeys and apes whenever I had a chance or felt financially free enough to lay out the funds for these animal actors, with their attendant trainers and handlers. The project has taken about five years to complete and the subjects were photographed at my studios in New York and Los Angeles, as well as at Parrot Jungle in Miami. In all, I have photographed more than thirty different primates, about twenty different species: marmosets, mandrills, capuchins, macaques, orangutans and a chimpanzee, to name a few. They all have resonated with me in different ways. I love the wisdom in the face of Jake, the older orangutan. He is only five years old but looks like an old man. Another favorite is Josh, the Celebes macaque, who is on the cover. His black hair, amber-colored eyes, and long face make him look almost unreal, like a cartoon character.

What became apparent as I was making my selections after each shoot was that I was attracted to the images where the subjects appeared almost human, expressing emotions and using gestures I thought were reserved only for people. The formal studio portrait setting adds an air of both seriousness and humor. Some people have commented that the animals resemble friends or relatives. Sharon Stone remarked as I was shooting her, that she has “sat in studio meetings with guys like that,” referring to “Haughty”. Indeed, monkeys are not as high maintenance as many of the subjects I regularly photograph, albeit markedly more difficult to communicate with and give direction to. Of course, with primates, I don’t have to be concerned with making sure they look “beautiful” or retouching them to appear flawless. They are us and the opposite of us at the same time since they share none of our cultural constraints on behavior or appearance. They seem to be looking back at us, sometimes judging, sometimes in shock. Is it something we’ve done? Maybe it is just that some of us are trying to pretend we aren’t related. For anyone who doubts Darwin (ahem, Mr. President), look in the monkey mirror and think again.

-Jill Greenberg, 2004

Ursine

URSINE

Ursine

URSINE